His speech is peppered with the language of democratic governance (“free choice”, “full consent”, “the popular vote”) – and he famously declares, “Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heaven”. By contrast, Satan has a dark charisma (“he pleased the ear”) and a revolutionary demand for self-determination. Ricks notes that Paradise Lost is “a fierce argument about God’s justice” and that Milton’s God has been deemed inflexible and cruel. Paradise Lost is an attempt to make sense of a fallen world: to “justify the ways of God to men”, and no doubt to Milton himself. It was a year of public and private grief, marked by the deaths of his second wife, memorialised in his beautiful Sonnet 23, and of England’s Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, which precipitated the gradual disintegration of the republic. When Milton began Paradise Lost in 1658, he was in mourning. William Blake, the most brilliant interpreter of Milton, later wrote of how “the Eye of Imagination” saw beyond the narrow confines of “Single vision”, creating works that outlasted “mortal vegetated Eyes”. As the philosopher Descartes wrote during Milton’s lifetime, “it is the soul which sees, and not the eye”. He invokes Homer, author of the first great epics in Western literature, and Tiresias, the oracle of Thebes who sees in his mind’s eye what the physical eye cannot. In Paradise Lost, Milton draws on the classical Greek tradition to conjure the spirits of blind prophets.

#Paradise lost text series#

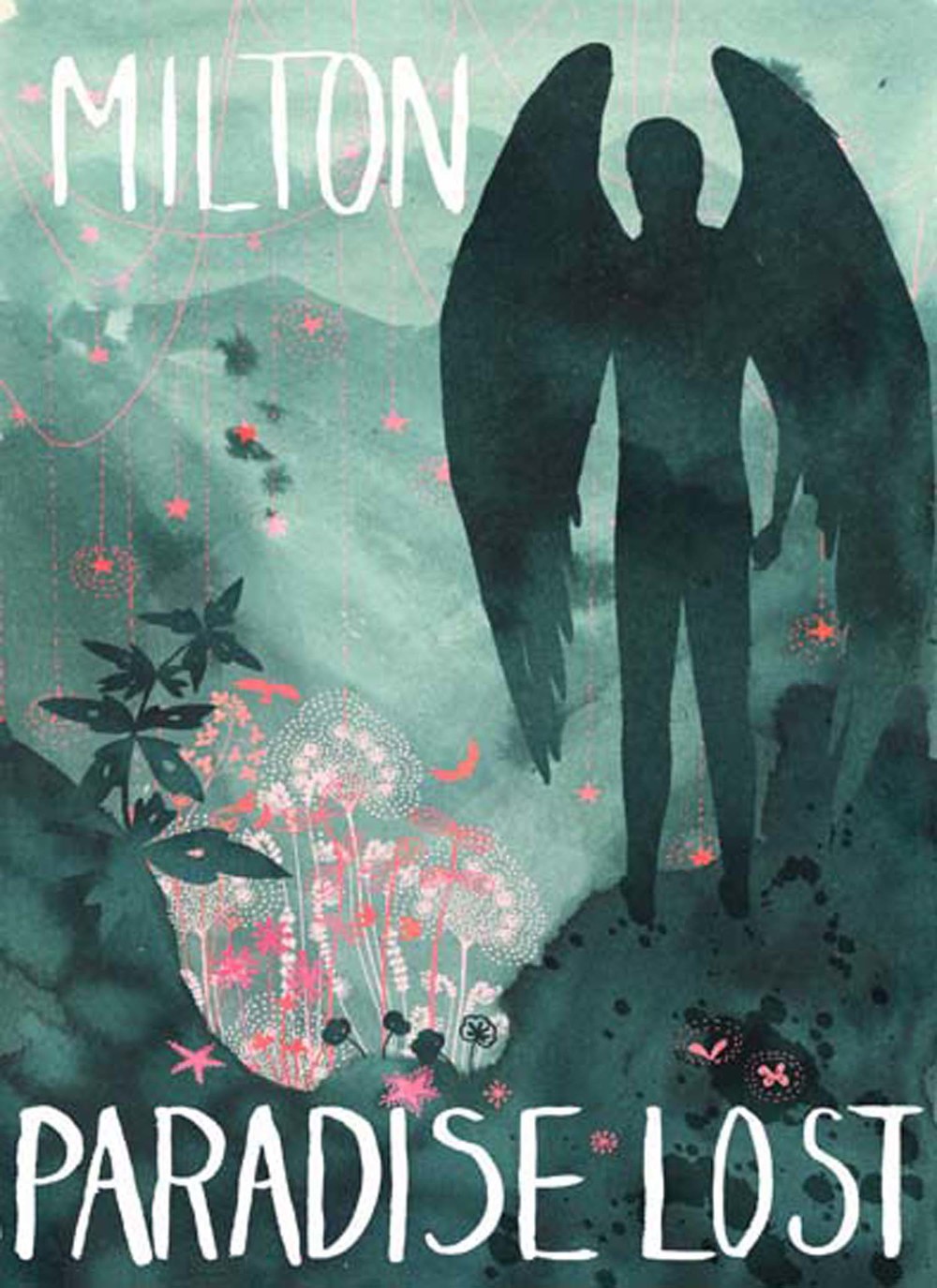

For the final 20 years of his life, he would dictate his poetry, letters and polemical tracts to a series of amanuenses – his daughters, friends and fellow poets. But his deteriorating eyesight limited his diplomatic travels. Milton gained a reputation in Europe for his erudition and rhetorical prowess in defence of England’s radical new regime at home he came to be regarded as a prolific advocate for the Commonwealth cause. (He wrote poetry in English, Greek, Latin and Italian, prose in Dutch, German, French and Spanish, and read Hebrew, Aramaic and Syriac). A committed republican, he rose to public prominence in the ferment of England’s bloody civil war: two months after the execution of King Charles I in 1649, Milton became a diplomat for the new republic, with the title of Secretary for Foreign Tongues. Even to readers in a secular age, the poem is a powerful meditation on rebellion, longing and the desire for redemption.ĭespite being born into prosperity, Milton’s worldview was forged by personal and political struggle. Its dozen sections are an ambitious attempt to comprehend the loss of paradise – from the perspectives of the fallen angel Satan and of man, fallen from grace. In more than 10,000 lines of blank verse, it tells the story of the war for heaven and of man’s expulsion from Eden. But this epic poem, 350 years old this month, remains a work of unparalleled imaginative genius that shapes English literature even now. Milton’s Paradise Lost is rarely read today.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)